The new road link would, the experts say, create a “corridor of opportunity”. It would “relieve congestion”, “improve accessibility” and “be of inestimable benefit to the capital”. It will, one supporter argues, “take longer-distance traffic off the existing main roads… enable cars and lorries to get from one side of London to the other without having to go through the centre; and… enable traffic to get to where it wants in London without having to drive endlessly through residential and congested streets.”

The new road link would, the experts say, create a “corridor of opportunity”. It would “relieve congestion”, “improve accessibility” and “be of inestimable benefit to the capital”. It will, one supporter argues, “take longer-distance traffic off the existing main roads… enable cars and lorries to get from one side of London to the other without having to go through the centre; and… enable traffic to get to where it wants in London without having to drive endlessly through residential and congested streets.”

Anyone worried about the new road’s noise and environmental impact can relax: there will be “generous compensation [for] those living close enough to it to suffer additional noise or loss of amenity.” Far from “affecting the environment adversely, it will in fact improve it.” It’s time to stop dithering, says a supporter of the new link: “There can be arguments… over the wisest routes; there can be postponements and prevarication. But in the end the nettle must be grasped, if London is to breathe and thrive.”

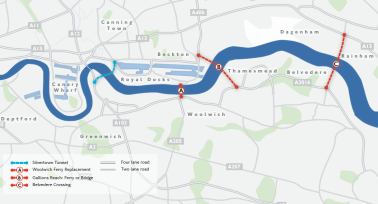

Any Londoner taking an interest in TFL’s current proposals for a new road tunnel under the Thames at Silvertown, just downriver from the Blackwall Tunnel, and new road bridges over the Thames at Gallions Reach and/or Belvedere, might assume that these are excerpts from the ongoing consultation (respond quickly if you haven’t already done so: it closes on December 19). But you’d be wrong: all these quotations are taken from politicians advocating a “Motorway Box” around inner London, which would have entailed the demolition of much of Camden Town, Blackheath and Brixton, in the early 1970s.

The Blackwall Tunnel Southern Approach – shown in black on this brochure from the late 1960s – was supposed to form part of Ringway One, a “Motorway Box” around inner London that would also have driven a six-lane highway through Blackheath Village

There’s an eerie similarity between the rhetoric deployed in favour of an abandoned motorway scheme 45 years ago and the rhetoric deployed by TFL in favour of new river crossings in east London in 2014. Just like the GLC then, TFL now promises that new roads “will greatly reduce delays”, “considerably reduce the time users spend stuck in traffic” and “make the wider area more attractive to businesses and developers, supporting growth in one of the most deprived areas of the country”. The belief that new motorways in inner London can deliver any of these benefits was, supposedly, debunked in 1973 when Labour won control of the GLC on a “Home before Roads” ticket and immediately cancelled the Motorway Box (or “Ringways” as they had been innocuously renamed) after only three small sections had been built (in Shepherd’s Bush, North Kensington and south of the Blackwall Tunnel).

Cost and controversy have meant that no significant new motorways have been built in inner London since then. No new road bridges or tunnels have been built over or under the Thames since the widening of the Blackwall Tunnel in the late 1960s. New roads that have been built have generally been new bypasses in the outer suburbs, or short new links (such as the Limehouse Link, to better connect Canary Wharf to the rest of London).

So you have to admire the chutzpah of Transport For London – going through the motions of an extensive “consultation” on a new motorway that is, as near as damn it, already almost certain to be built. The Silvertown Crossing has been deemed a “Nationally Significant Infrastructure Project” which will probably be approved by an Infrastructure Planning Commission and a secretary of state in early 2017. Although there will be “hearings” before then there won’t be a public enquiry, let alone a vote by councillors in the boroughs effected or the residents they represent. Even the London Mayor, who chairs TFL, will not get a look in. Given the seeming inevitability of the tunnel you have to admire the determination of the No to Silvertown Crossing campaign, which is warning that the tunnel will only worsen air pollution and congestion and is still fighting hard to stop it.

How have new road crossings become such a foregone conclusion? Why does it looks increasingly likely that at least two new motorways will soon cross the Thames – a road-building programme that would be unthinkable in any other part of the capital? Why is east London treated differently from everywhere else?

The case for Silvertown, and other river crossings further east, is easily made. It’s often said that a new river crossing, or two, in East London was first proposed in 1943, when Patrick Abercrombie published his County of London Plan for the rebuilding of the capital after World War Two. But in fact they were first floated even longer ago, in Sir Charles Bressey’s 1937 Highway Development Plan for Greater London.

Abercrombie’s ‘Road Plan’ does indeed show a highway crossing the Thames almost exactly where the Gallions Reach bridge is now proposed, as well as a widened crossing at Blackwall with a motorway to the south (the present day A102/A2). A second bore at Blackwall with new feeder motorways were built in the early 1970s but the lower Thames crossing was repeatedly deferred from the 1960s onwards, as was a third bore at Blackwall. So there’s a compelling argument that a road crossing at Thamesmead, and further capacity at Blackwall, are missing pieces in the jigsaw of post-war planning, and that with more and more development in east London it’s high time they were slotted into place.

The innermost Ringway One caused so much controversy in the early 1970s that the planners didn’t have a chance to get on to Ringway Two, an orbital motorway to replace the North and South Circular roads which would have crossed the Thames at Thamesmead (for a full account of the Ringways controversy, the CBRD website is recommended).

When detailed proposals were put forward for a Thamesmead bridge, by then rechristened the east London River crossing or ELRIC for short, in the mid-1980s they turned out to be just as controversial as any of the Ringways had been. A glance at Abercrombie’s map shows why: his Lower Thames Crossing (which would have been a tunnel, not a bridge) entailed a new motorway running southwards across Plumstead High Street (where its fire station still stands, on the corner of Lakedale Road), bisecting Plumstead Common and then running over Shooter’s Hill and through the ancient Oxleas Wood to connect to the A2 at Falconwood. ELRIC would have brought a very similar southern access road, following the course of Wickham Lane slightly to the east of where Abercrombie had proposed, but still cutting Oxleas Wood in two. I’m too young to have been actively involved in the People Against the River Crossing (PARC) campaign, which Labour enthusiastically backed, but I can clearly remember the visceral anger that people felt about a motorway ploughing through Plumstead and an ancient woodland. The plans for ELRIC were finally shelved in 1993 after – Eurosceptics take note – a threatened legal challenge by the European Commission (see here for an excellent account of the campaign on the e-Shooter’s Hill website).

But it was only three years before the project was revived. In April 1996, in the dying days of John Major’s government, Transport minister Steve Norris (who went on to be the Tory Mayoral candidate in 2000 and 2004) unveiled plans for a new package of east London river crossings: an additional road crossing at Blackwall, a rail tunnel at Woolwich, and a “multi-modal local crossing” between Beckton and Thamesmead, later dubbed the Thames Gateway Bridge (TGB). Remarkably, by omitting a motorway southwards through Oxleas Wood the TGB escaped strong opposition either from local residents or from east London’s (mostly Labour) politicians. There was vociferous opposition from national environmental groups like Friends of the Earth but no big community campaign against the TGB, and above all little or no opposition from the Labour party either in Greenwich at the southern end of the bridge, or Newham to the north. In a reversal of the reaction to ELRIC in the 1980s, the strongest political opposition to the TGB was from Conservative councillors in the neighbouring borough of Bexley.

When Ken Livingstone became London’s first elected mayor in 2000 he enthusiastically backed the TGB plan he inherited. It is supremely ironic that Ken – a supposedly car-hating, independent left and later Labour mayor – backed a bridge at Thamesmead that his Tory opponent had proposed five years earlier. Indeed if anything the bridge that Ken pushed for was even less environmentally friendly than what Steve Norris had proposed in 1996. Rather than a truly “multi-modal” bridge bringing a badly-needed rail or DLR link to Thamesmead, Ken’s bridge promised only bus lanes with no guarantee over the frequency or routing of the buses that would use them. Nor was there any guarantee that the bridge would be accompanied by the rail crossing at Woolwich that Norris had promised (although Woolwich has since got a DLR link and now has Crossrail to look forward to, neither were in the bag when Ken relaunched his TGB proposals in 2001). Greenwich Council argued for higher tolls for long-distance traffic and added half-hearted demands for a tram or DLR link from Beckton to Thamesmead, but otherwise backed the bridge enthusiastically.

Why the change of heart? Stubbornly high levels of unemployment in east London and continuing difficulties in attracting inward investment (particularly south of the river in Bexley and Greenwich, which had not benefitted from the London Docklands development Corporation in the 1980s and 1990s) meant that environmental concerns about the impact of a new road crossing were swept aside. In Greenwich this had some unpleasant consequences in the early noughties. Many people in the council had decided that the bridge was a magic solution to Thamesmead’s isolation and economic stagnation, to back it come what may, and to either ignore opponents or prevent them from having their say, even at internal Labour Party meetings.

At one meeting, Labour stalwart Barry Gray (a key member of the anti-ELRIC campaign in the 1980s and 1990s) was barred from speaking, supposedly because of an oversight by the chair. Many people – myself included – thought this was no accident, but just part of an organised attempt to silence critics. A proposed investigation into the TGB by Greenwich’s all-party scrutiny committee was strangled at birth, and a council employee who campaigned against the bridge in his spare time was threatened with disciplinary action.

This Artist’s Impression of the Lower Thames Crossing, proposed by Steve Norris in the mid-1990s, shows dinky trolley buses running on dedicated lanes with overhead cables – a commitment that was later dropped

That the Thames Gateway Bridge bit the dust was because of the intricacies of the planning process, not because of political or community opposition: while there were several dissenters within the Labour Group on Greenwich Council they were easily outnumbered by those who backed the bridge. The Secretary of State called a public inquiry in 2005 which found several faults with the scheme, not least that having three lanes of traffic in each direction was not consistent with the local road networks on either side of the river. The consultation carried out by TFL in 2003 was criticised for failing to consider alternative options, and the potential environmental impacts. The Secretary of State asked the Mayor to address the inspector’s concerns and the bridge was redesigned, but by this point it had, belatedly, generated some well-organised opposition. TFL promised that the bridge would be “local link” with a 40mph speed limit and bus lanes that “could be upgraded for use by trams or DLR in the future if needed”, but London is littered with such broken promises. Many people feared, understandably, that the TGB would just end up as an alternative to the Dartford Crossing and that long-distance lorry traffic would overwhelm it.

In 2007 a new Secretary of State, Hazel Blears, reopened the public enquiry and in 2008 the newly-elected Conservative Mayor of London, Boris Johnson, cancelled the Bridge completely. Boris’s decision had little to do with environmental sustainability. Although Boris said he was cancelling the TGB to save money, it was an open secret in south-east London that Boris was returning a political favour to Bexley (whose residents had overwhelmingly backed him in 2008 and whose Tory-controlled council was implacably opposed to the TGB because of the traffic impact, and fears that a new link road through Oxleas Wood to the A2 would have to built later).

Thus Boris only entrenched support for river crossings among many Labour politicians in east London: not only had he cancelled a vital regeneration project, he had done so for the basest of political motives.

*****

Six years on, Boris is now enthusiastically backing a Gallions Reach bridge almost identical to the TGB proposal he canned in 2008, which says much about his opportunism and lack of backbone. Opposition to a new bridge in Bexley seems to have been allayed by an alternative option for a new crossing at Belvedere, which would be closer to the M25 and would therefore create less pressure for a new orbital road southwards through Oxleas Wood to the A2. For once there is now a remarkable political consensus between most Labour and Conservative politicians in east London: both parties support a tunnel at Silvertown and a bridge at Gallions Reach and/or Belvedere. The only quibble from most Labour politicians is that Boris is building them too slowly.

But this cosy consensus should not blind us to the flawed logic behind what is now proposed and the potentially disastrous environmental impacts. Much earlier debate about the pros and cons of new river crossings has generate more heat than light. It’s time to take stock of why we are here.

1 Supporters of river crossings exaggerate the benefits and twist the facts

Even if the new Silvertown Crossing does remove traffic jams from the A2 and A102, as its supporters claim, it’s ludicrous to think that air pollution will magically disappear. Although 40mph is the optimum speed (cars travelling any faster than that emit more pollution) it’s a myth that fast-moving traffic generates less pollution than a traffic jam: sometimes vehicles stuck in traffic jams turn their engines off. Equating speed of traffic with environmental sustainability is the logic of the madman, and shows that road rage causes misjudgement long after the traffic jam has subsided. New roads almost always generate more traffic, and more congestion, than forecast and it’s not clear why any of the proposed crossings will be exceptions to the rule.

Those calling for new crossings always contrast the high density of bridges over the Thames in West London with their scarcity in east London. They argue that west London’s economic prosperity is directly linked to its many bridges, and that increasing the number of road crossings in east London is essential if it’s ever going to catch up.

TFL makes much of the fact that East London has far fewer road crossing than west. But is that necessarily a problem?

But this is to confuse cause and effect. West London has many bridges because it has, since the early nineteenth century, been a residential overspill of London in which many historic towns – Chiswick, Richmond, Kingston, Barnes, Putney, Hammersmith and others – face directly onto the river.

In East London, bridges were not built in the nineteenth century for three simple reasons. Firstly there was limited demand (most dockworkers did not drive and could commute just as easily by foot tunnel, and most industrial traffic to and fro was on the river itself). Secondly the Thames is of course two or three times wider in east London than in west, and consequently more costly to bridge (a high clearance also needs to be provided so that shipping can pass underneath any new bridge). A third reason is that for centuries the main land use on its banks was docks and industry, not housing. Since the decline of the docks many new riverside homes have been built, but other riparian land uses (refuse disposal, sewage works and prisons) do not sit well alongside homes. With just three exceptions – Greenwich, Woolwich and Erith – all of east London’s main settlements still turn their back on the river (despite its name, Thamesmead is separated from the river by a huge wall, and even in Woolwich the river has to be hunted down as views of it are blocked by a hulking 1980s leisure centre).

The main reason why the Thames Gateway does not capture the public imagination (indeed, the phrase is hardly ever heard outside the regeneration industry) is that the banks of the Thames are frontiers, not gateposts.

What’s more, the difference between the density of river crossings in east and west London is exaggerated. The covering letter that comes with TFL’s current consultation document for the Silvertown Link says “there are only two crossings in east London”, which is simply untrue. If you define “east London” as the Thames between Tower Bridge and Dartford, and if you count the London Overground, Jubilee Line, Docklands Light railway and foot tunnels, there are in fact 11 river crossings, not two (from west to east: the Rotherhithe road tunnel, the London Overground between Wapping and Rotherhithe, the Jubilee Line between Canada Water and Canary Wharf, the DLR between Island Gardens and Cutty Sark, the Greenwich Foot Tunnel, the Jubilee line between Canary Wharf and North Greenwich, the Blackwall Tunnel, the Jubilee line between North Greenwich and Canning Town, the Woolwich Ferry, the Woolwich Foot Tunnel, and finally the DLR between King George V and Woolwich Arsenal). TFL, tellingly, seems to define “river crossings” as road links, and even these are undercounted. East London already has many river crossings. Most of these are not road crossings, but is that a bad thing?

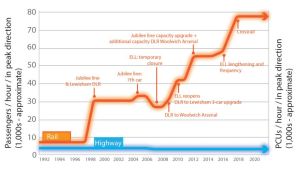

This TFL chart shows how public transport connectivity across the Thames in east London has improved since the 1990s, while road capacity has stayed the same. But isn’t that the sort of “Modal Shift” that transport planners should be proud of?

It’s sometimes argued that a new road crossing or two is need to “redress the balance” because east London has benefitted so much in recent years from new public transport links (the Jubilee Line, DLR extensions to Greenwich and Woolwich, the pointless Emirates Airline cable-car, and Crossrail to come) but has not been given any new road crossings. This is to misunderstand the demographics of east London. Three of the four boroughs that would be connected by the proposed new road crossings are among the 20 local authorities with the lowest levels of car ownership in the UK. In Tower Hamlets 63% of residents do not own a car, in Newham 52%, and Greenwich 42% (leafier Bexley has a car ownership rate of 76% overall but this is much lower in the poorer, northern part, whose residents would bear the brunt of new road crossings at Thamesmead or Belvedere).

Even in prosperous areas like Blackheath a good 35% of households have no car. And anyone who thinks that car ownership is bound to go up in future should remember that in fact it fell in all these boroughs between 2001 and 2011 (in Tower Hamlets it fell by a hefty 14%). People are choosing not to have cars not just because of affordability, but increasingly as a lifestyle choice: driving and parking in London is just too much hassle.

And west London’s many bridges are a curse as well as a blessing. A friend who lived next to Joseph Bazalgette’s Hammersmith Bridge in the late 1990s was delighted when it had to be closed for structural repairs: air pollution was reduced, people walked and cycled more, enjoyed the river views in peace and spoke to their neighbours. West London’s bridges had been built for the horse and cart rather than the internal combustion engine, and suddenly the best thing about the bridge was the absence of motor traffic.

Cars coming up to the toll gates at the Dartford Crossing. Despite increases in tolls for long-distance users, hefty discounts for local drivers encourage unnecessary journeys and add to the tailbacks

Another east-west contrast is often drawn: why should poor east Londoners have to pay tolls to cross the river when rich west Londoners can cross their bridges for free? Even those who oppose new river crossings have fallen for it. Bizarrely, the environmentalist John Whitelegg (of whom more later) has opposed tolling either Blackwall Tunnel or any new crossings, asking rhetorically “Is it fair to institute toll crossings in a poor part of London and not further west where affluence levels are much higher?”

The answer to Whitelegg’s question is clearly yes: the higher density of river crossings in west London isn’t a cause of its affluence but a consequence, and the poorest people in east London don’t own cars. Ideally, there should be a London-wide congestion charge which would hit west and east London motorists equally hard, but you have to start somewhere.

It’s often assumed that new Thames crossings will act as a magic wand to revive stalled development schemes. In 2003 it was forecast that East London would see 142,000 new homes and 255,000 new jobs by 2016: in reality only a fraction of these have materialised. But the stalling of developments such as Barking Riverside and Thamesis Point (formerly known inelegantly as Tripcock Point) in Thamesmead in the noughties had more to do with the credit crunch, and the lack of DLR or rail connections, than the lack of road links. And although none of them go over the river Thamesmead and Barking have no shortage of motorway-standard roads: the A13 goes east-west through Barking and the A2016 east-west through Thamesmead.

Thamesmead faces lots of problems. Blaming them all on the lack of a road bridge across the Thames is nonsense

There are a number of uncomfortable reasons why places like Thamesmead have never really succeeded. Its division between two London boroughs (Greenwich and Bexley) means that both regard the place as a peripherally low priority. Relatively low property prices have attracted buy-to-let landlords, many of them unscrupulous, who let out damp and overcrowded flats to low-income, high-turnover tenants. Decades of poor planning decisions, initially by the GLC and more recently by the two boroughs, have girdled the place with roundabouts, soulless retail sheds, cul-de-sacs of rabbit-hutch houses and woefully poor pedestrian and cycle connections (I once tried to get from Thamesmead to Woolwich without walking along the river; the only pedestrian route I could find ended up on the hard shoulder of a motorway).

For politicians who have presided over many of these mistakes – as I have – the lack of river crossings is a very convenient scapegoat for Thamesmead’s manifold problems. Anyone with even a basic understanding of London knows that to compare Thamesmead with Hammersmith is to compare chalk and cheese: the absence of Thames bridges in east London is just one of many geographical, economic and social differences between the two. To argue that building bridges would miraculously regenerate east London is absurd.

2 Having told critics to shut up for so long, Labour’s u-turn on the crossings may be too late

2 Having told critics to shut up for so long, Labour’s u-turn on the crossings may be too late

A consistent problem has been the rewriting of history and the marginalisation – or simple exclusion – of people with legitimate doubts about river crossings. The control freakery that hovered over the TGB proposals in the early noughties only intensified once the current proposals for river crossings emerged in 2012.

I attended a meeting of Greenwich’s Labour councillors to discuss Boris Johnson’s new river crossing proposals in late November 2012. Most of them (me included) expressed a lot of ifs, buts and maybes and said they would only support new river crossings if they brought the DLR or heavy rail, and only if environmental studies produced definitive evidence that they would reduce air pollution rather than increase it.

But all these caveats were quickly forgotten. I still have a yellowing copy of the December 4th 2012 issue of Greenwich Time with which a crude “Bridge the Gap” campaign was launched the following week. Astonishingly, the story made absolutely no mention of air quality, the council’s longstanding call for the DLR to be brought through the Blackwall Tunnel to Eltham, or tolling. The public was now being wrongly told that their councillors just wanted to “Bridge the Gap” with new road crossings at all costs. The campaign was not just wrong in environmental and transport terms, but politically inept. By expressing uncritical support for Boris Johnson’s river crossings proposal (with just one proviso: the council backed a bridge rather than a ferry at Thamesmead) Greenwich at a stroke lost all leverage with the mayor.

Labour councillors who expressed concerns about the ridiculous “Bridge the Gap” campaign – which no-one knew about in advance apart from the council’s then leader, Chris Roberts – were, incredibly, told they had voted for it. Grassroots Labour members, most of them hostile to new crossings, were told that they have to back the Silvertown Link and a new bridge at Thamesmead as it had always been Greenwich Labour’s policy to support more river crossings. This isn’t even half true – the Labour party in Eltham is opposed to a bridge at Thamesmead (because of residual fears about a new motorway through Oxleas Wood) and is lukewarm at best about a Silvertown Link. In the Greenwich and Woolwich constituency there’s neutrality about a Thames Gateway bridge, a sentimental reluctance to see the Woolwich Ferry closed, and a lot of outright opposition to a Silvertown link.

The A102 motorway passes within a few feet of homes on Siebert Road and Westcombe Hill. But for 40 years TFL have refused to put a proper fence up

Two years on it’s difficult to overstate the anger that many Labour councillors felt about Bridge the Gap. In my case, the No to Silvertown Tunnel campaign found that the worst air pollution in Greenwich – 104 µg/m³ of nitrogen dioxide, almost three times the EU legal limit – was by the Siebert Road foot-tunnel under the Blackwall Tunnel approach road (in the ward I represented until May 2014, and within 200 metres both of my childhood home and the two primary schools I attended in the 1980s). For many years residents of Siebert Road and Westcombe Hill, who live just a few feet from the hard shoulder of the A102, have been asking for modest fencing to be put up (interest declared: my partner Liz used to live on Westcombe Hill, albeit a decade ago). TFL – under both Ken Livingstone and Boris Johnson’s leadership – has consistently refused, arguing contemptuously that the requirement for fences alongside motorways only dates from the 1980s and does not apply retrospectively to a motorway built in the early 1970s. I urged the council to say that before a Silvertown tunnel could even be considered TFL must do something – but to my fury the council’s response to TFL did not even mention the problem, let alone demand a solution. (To add insult to injury, Greenwich Time even carried a front page photo of homes on Siebert Road next to the usual A102 traffic jam.)

Within a few weeks of the campaign’s launch the council was already rolling back, claiming that “Bridge the Gap” was just a public awareness campaign to alert residents to the consultation, not to express unconditional support for motorway bridges. But the damage was already done. An online poll on the council’s website registered all those responding as supporters of the bridge, and convinced no-one. By the time of the 2014 elections many Labour councillors and candidates were in open revolt, telling hustings meetings that they would only support any new tunnel or bridge if it could be proved that air pollution would be reduced – a tall order that TFL will struggle to meet.

Since a change of Leader after the May election Greenwich’s Labour Council has performed a welcome u-turn. There’s no more “Bridge the Gap” rhetoric. The council’s Labour group held a special meeting in September to thrash out its position on river crossings , with workshops and both pro- and anti- speakers from outside the council making their case. In 2013 the council refused to make its assurances about air quality, or new rail or DLR links, a conditional of its support for be river crossings; now it says it is “imperative” that a new bridge at Gallions Reach “has dedicated public transport provision, and is part of a wider package of dedicated rail transport crossings… to Thamesmead and Abbey Wood”, and confirmation “the bridge would not worsen local traffic levels or air quality.” In 2013 the council had argued, absurdly, that there was no need to commission any air quality impact assessments as TFL’s first consultation on river crossings in 2012-13 was “high level” and that the council could rely on TFL’s own assessments later (as TFL’s traffic, congestion and air quality forecasts for the TGB a decade ago were later shown to be laughably wrong, this cut little ice with anyone).

The council is now arguing both for a London Overground extension from Barking Riverside to Abbey wood via Thamesmead, and a DLR link to Thamesmead as well – hedging its bets in the knowledge that the council would do well to get one of these and is unlikely to get both. The council now says that “it wouldn’t support any widening of the A2”; in 2013 there was no such assurance. Greenwich’s pollution readings, which went mysteriously offline once the council launched its “Bridge the Gap” campaign, can now be viewed again on the council’s website.

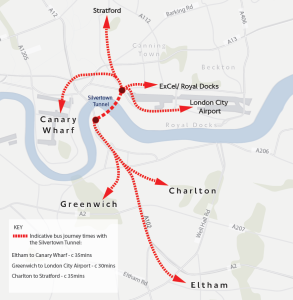

Not good enough: TFL is only making vague promises of new bus links through the Silvertown tunnel, not the DLR or the London Overground

At the hustings where he was selected as Labour’s candidate for Greenwich and Woolwich last year, Matthew Pennycook – who will almost certainly become its new MP next May – said he would not back a Silvertown Link “unless it improves air quality”. Refreshingly, Matt wrote on Greenwich.co.uk last week that he “still remains to be convinced” by the case for Silvertown: a brave stance given that it is still backed by many current Labour MPs, the Labour group on the London Assembly, and Greenwich Council (albeit more reluctantly than last year). Very sensibly, Dartford’s Labour candidate Simon Thomson is campaigning against an extra road crossing there – he’s rightly realised that it would only bring more traffic gridlock, not less.

The Labour council in Greenwich will not perform a second u-turn and state unconditional support for road crossings without a huge dust-up internally. But given the blank cheque that Greenwich Council signed in 2013 I fear it is too late. TFL’s decision to hold two consultations – one on crossings at Woolwich, Gallions Reach and Belvedere that closed on September 12th, and the current consultation on Silvertown, which runs until 19 December – smacks of divide and rule and senior figures in Greenwich Council admit privately that it’s “a sham”. Rather than a “package” of crossings TFL now seems to want to press ahead with Silvertown with or without any river crossings further east. Greenwich could end up with the worst of both worlds: a new tunnel at Silvertown attracting more and more traffic onto the A102, and no prospect of a bridge bringing the DLR or Overground to Thamesmead.

As this map shows, many car trips through the Blackwall Tunnel aren’t local – they start and finish much further afield than Greenwich

3 The “local crossing” myth still persists

TFL and the backers of river crossings always claim that they would mostly be used by “local” people, who overwhelmingly support them. The facts don’t support this argument. Those responding to TFL’s consultation back in 2012-13 were, overwhelmingly, drivers who cross the river by car rather than public transport (more than half the Greenwich responders said they crossed the river at least once a week by road). Unsurprisingly three quarters of them said they support a new road crossing at Silvertown. What’s more, the response rate was very low: only 2,194 responses from Greenwich residents were received (less than 1% of the borough’s population of 255,000). Similarly a survey by TFL in 2001, which supposedly showed 71% support for the Thames Gateway Bridge, had an equally tiny sample: only 1,508 people responded (about 0.1% percent of the population of the six riparian boroughs the survey covered). Further consultation in 2003 elicited more responses – 5,290 to be precise – but of these a whopping 74% “said they expected they would cross the bridge by car” and, unsurprisingly, 85% backed the bridge. A proper survey of a representative sample of east Londoners – reflecting that, as in other boroughs, nearly half of Greenwich households don’t even own a car, let alone use one daily – would produce very different result. But TFL hasn’t bothered to conduct one.

TFL asserts that “Trips using the Blackwall and Silvertown Tunnels are mostly local journeys (defined as having at least one end in Tower Hamlets, Newham, Barking and Dagenham, Havering, Lewisham, Greenwich or Bexley)”, but is reluctant to give more detail: all its voluminous “Needs and Options” analysis says is that”75% of all trip origins and 83% of all trip destinations lying within Greater London” (see here). In fact, TFL itself acknowledges that the Blackwall Tunnel, and the proposed Silvertown Link beside it, are “strategic” rather than local crossings, with much northbound traffic originating in the Medway/Maidstone area “from where the A2 and Blackwall tunnel provide a convenient route to Docklands and central, north and east London”. Any new Silvertown crossing will only attract more long-distance traffic that should bypass London entirely. What economic value Greenwich derives from long-distance lorries en route from Maidstone to Enfield is beyond me.

Those Greenwich residents who do commute by car through the Blackwall Tunnel are a vociferous minority who argue that their journeys are essential and unavoidable. Labour should have the courage to stand up to these residents. Rather than make false promises of big toll discounts for local drivers (which TFL is unlikely to grant) the council should be arguing for better cross-river and DLR links to get these people out of their cars. The kind of local discounts that the Dartford crossing offers (local residents get 50 free crossings for an annual registration fee of £10 with additional crossings at just 20p each, or unlimited crossings for an annual fee of just £20 annually) only encourage unnecessary cross-river car journeys.

The proposed Thames Estuary Airport may not have been popular locally, but it would have brought new public transport infrastructure that will now be more difficult to secure

4 Consultation fatigue, and opponents overplaying their hand, has bolstered support for new crossings

It’s now more than 75 years since Sir Charles Bressey first proposed a tunnel under the Thames at Thamesmead, and 35 years since ELRIC was mooted in 1979. Most people are now thoroughly fed up with discussions about East London river crossings and either want them built, or ruled out for good, without any further delay.

The problem is that everyone is so busy concluding unfinished business from the twentieth century to stop and think about whether road crossings planned are the right answer to London’s twenty-first century challenges . Even the Guardian – which can normally be relied on to be sceptical about road-building – recently ran a piece by Oliver Wainwright generally uncritical of a bridge at Thamesmead, unquestioningly reporting TFL’s promise to build the Silvertown Tunnel by 2021. A “Just get on and build them” mentality has set in. Many of the criticisms of the current proposals are merely quibbles about timing – people just want the bridges built more quickly than Boris says they can be (in 2003 the Thames Gateway London Partnership said that completing the Silvertown Link by 2015 would be “too late”; it now turns out that completing it by 2021 is pushing it).

But it’s also true that some of the opponents of river crossings have obscured good arguments with exaggeration and hysteria. Just as dangerous as dogmatic support for motorways across the Thames is dogmatic opposition to any river crossings that may include provision for the private car. When he was proposing the Thames Gateway Bridge in the early noughties Ken Livingstone was often heckled by fanatical opponents (I once sat next to them as they shouted “war criminal” at Ken at a public meeting, which hardly helped their case).

In 2002 John Whitelegg, a transport consultant and later a Green councillor in Lancaster, published a report which denied that cross-river links, of any kind, could drive inward investment and create jobs. “The best solution to unemployment in Greenwich is more jobs in Greenwich.” Whitelegg argued bizarrely, suggesting that east London boroughs should be self-contained labour markets, not part of the London-wide economy, and travel between boroughs should be discouraged. He concluded that the river crossings were based on the “fatally flawed concept that providing new infrastructure to improve accessibility can automatically be translated into new local jobs of the kind that will assist in regenerating deprived areas of east London…. Not only will these jobs not be created but the environmental quality and health of local residents will be further damaged.”

Whitelegg was not just raising legitimate concerns about new road crossings, but also espousing a flat-earth philosophy which saw all human movement as somehow suspect, at least for poor people who could not possibly benefit from new jobs on the other side of a river. Based in Lancaster (300 miles from London), Whitelegg argued that east Londoners’ horizons should not extend beyond the borough in which they live. Politicians rarely listen to such humbug and hyperbole.

The No to Silvertown Campaign has avoided most of these pitfalls: I admire the work that Darryl Chamberlain and others have put in (Darryl’s devotion to the campaign is such that he has temporarily paused his 853 blog’s running commentary on the swings and roundabouts of Greenwich politics). But the campaign could be more forthcoming with alternatives to road crossings, and is on shaky ground opposing a bridge at Gallions Reach that could being the DLR to Thamesmead (this is not NIMBYism on my part: my home in Plumstead is much closer to the proposed Gallions crossing than to Silvertown).

****

In cities like Bremen, car-sharing schemes and excellent public transport is reducing car ownership – and car use. Why can’t we do the same in London?

Both the supporters of crossings – and many of their opponents – are guilty of tunnel vision. Supporters haven’t pondered why new river crossings in east London should make any provision for the private car (in other big cities, new infrastructure is often car-free). Opponents are too reluctant to admit that “smart tolling” can deliver greener road crossings, by penalising polluting cars and single-occupancy and rewarding car-sharers and low-emission vehicles. Technology has moved on a great deal, but the debate about river crossing still seems to be stuck in the 1980s. Opinion is polarised between those who argue that cars should flow freely and environmentalists who argue that there should be no provision for cars whatsoever : there are many, many shades of grey between these black and white extremes.

In 2013 the Centre for London set up a Commission on Thames Crossings, chaired by former Labour Transport Secretary Andrew Adonis, whose final report assumes that the Silvertown Tunnel is a “done deal” – all that remains to be done is to ensure that it is built on time and on budget. Further east, the commission supports new road crossing with only a few quibbles: it argues for a tunnel (rather than a bridge or ferry) at Gallions Reach, with dedicated bus lanes only four traffic lanes, not six – but it’s not clear how this will reduce pressure for a new road links southwards to the A2, or how long-distance traffic will be discouraged from using it. Urgency is stressed, given that the current Woolwich ferry is assumed to become redundant by 2024. The commission argues that a Belvedere bridge should be built as well as – not instead of – a Gallions crossing (TFL’s current consultation presents them as either/or options), and that a Belvedere bridge could include a rail link. But otherwise the report is almost silent on public transport. It asserts that the road network provides a “more uniformly-concentric and ‘predictable’ level of accessibility compared to public transport. This means that for many point-to-point journeys in Outer London, the car will remain the quickest and most attractive mode.”

The Centre for London’s recent report, calling on Boris Johnson to get on with building road crossings without delay, was a missed opportunity

Really? In fact dozens of cities around the world have grown and improved connectivity without building any new roads. Increasingly, European cities only welcome low-emission vehicles with more than one passenger. Two hundred cities across Europe now have Low Emission Zones in which polluting cars are either banned outright or subject to punitive tolls. In the German city of Bremen, 8,000 people are already signed up to a shared car scheme that is forecast to take 6,000 cars off the streets by 2020. High Occupancy Vehicle Lanes – reserved for cars with at least two passengers – are now the norm in many American, Scandinavian and Australasian cities. In Manchester, the Metrolink light rail system has led to a 21% shift away from car use. In car-loving California, San Francisco’s Bay Area Rapid Transit System has cut car traffic since its inception in the 1970s and now accounts for a remarkable 48% of all passenger miles in the area. Even in Los Angeles, a city that loves the car even more than San Francisco, households within half a mile of new Metro stations reduce their driving by an astonishing 10 to 12 miles a day. In Groningen in Holland, a determined policy to reduce car use has meant that a whopping 50% of all journeys are now by bike.

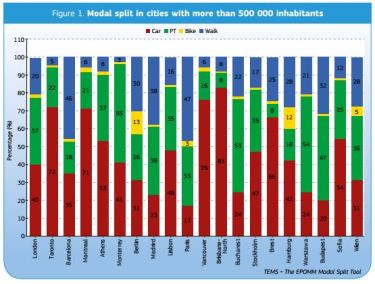

In terms of the split between car use and public transport, London still lags behind other European capital cities. Why make things worse?

But despite the great progress made by TFL in the last 15 years to introduce congestion charging, expand the bus, tube and DLR networks, make London more cycle-friendly and ban the most polluting HGVs, there’s still a rump of TFL traffic engineers who think that building new road capacity is the solution to east London’s transport problems. TFL argues that “there will always be a need for some journeys to be made by road, including by bus or for freight”, coyly neglecting to mention the private car. TFL’s consultation makes no mention of differential tolling based on cars’ emissions, or the number of passengers they contain.

Although London’s public transport has improved hugely since the 1990s, recent European Commission research shows that 40% of journeys in London are still by car – much higher than European capitals such as Paris (17%), Madrid (23%), Vienna and Berlin (both 31%). And while cycling has taken off in London in a big way in the last decade, London’s still far behind many other cities (an astonishing 57% of Amsterdammers use bikes every day). To imply, as TFL does, that public transport use in London has peaked, and that car ownership, and the number of car journeys, will inevitably rise is nonsense: many similar European cities have half the level of car use that London has.

TfL’s target to reduce the percentage of London journeys by private car or motorbike from 43% in 2006 to 37% in 2035 is far too modest. London currently uses the equivalent of two supertankers of oil to meet its energy needs. Air pollution already causes a staggering 4,000 premature deaths in London every year. With fuel prices rising, sea levels rising and an extra 1.3 million people expected to live in London by 2035 – half of them in the Thames Gateway – this just cannot be sustained.

There’s no reason why new homes and jobs should mean more cars on the road. If the bus and rail system is good enough people won’t need to drive and road crossings can be reserved for freight. Now that it is highly unlikely a Thames Estuary airport will be built it’ll be more difficult to ever get Treasury funding for a rail link from the Medway towns to Southend. But in inner London the £750m earmarked for the Silvertown crossing would be much better spent on DLR extensions and new rail links.

Many of my partner’s family live in Southend and we normally drive to see them: public transport involves either a long journey to West Ham on the DLR and then a train eastwards, or going all the way into central London and then out again. An orbital rail link from Woolwich or Abbey Wood northwards to Barking would mean we would leave the car at home. Look at how London Overground has transformed the connectivity, and reputation of, New Cross and Brockley and imagine if the same happened to Woolwich, Plumstead or Abbey Wood.

****

As the Campaign for Better Transport pressure group rightly says, proposed new road crossings “work against the positive direction of change in London travel patterns that was established in the 1990s and 2000s.”. Building new road bridges with little or no provision for public transport would be a big step back to the 1970s, not forward into the twenty-first century. Surprisingly little has been learnt in the last 45 years. The naivety of the Evening Standard, the Guardian and the many Labour politicians who all welcome the plans is staggering.

Far from opening up new jobs and “regeneration opportunities”, new road crossings in East London would only open up a Pandora’s box of environmental problems. Rightly or wrongly, south-east London has a road network far inferior to any other part of the capital. Away from the river there are few dual carriageways apart from the A102 and A2 and a few short stretches of the South Circular road. Elsewhere the road network is largely Victorian (the A2 and A20, the main roads from the channel ports to London since Roman times, converge at New Cross onto narrow streets that have not been widened since the early nineteenth century).

This CGI of the Gallions Reach bridge may look breathtaking, but in reality it would require mile-long ramps at either end to achieve the necessary 50-metre clearance above the Thames: hardly conducive to walking or cycling

South-east London’s antediluvian road network should be seen as a blessing rather than a curse: it should prompt us now to think more radically about how this part of London can be an exemplar of low-carbon sustainable transport, with car use reduced rather than just contained.

Some things have changed since the TGB was proposed back in the early noughties: councils like Greenwich are now more insistent that new bridges or tunnels bring the DLR or London Overground rather than just bus links; it’s now inevitable that tolling will apply to the existing Blackwall Tunnel as well as any new river crossings; TFL seem to be paying more than just lip service to concerns about rat-running, air quality and noise. But any new road capacity in south-east London will put intolerable pressure on the rest of the system, and with it pressure for more and more roads. Although the proposed bridge at Gallions Reach is no longer called the Thames Gateway Bridge it’s more or less the same TGB that was proposed by Ken Livingstone with “only” four lanes of traffic rather than six. It’s still unclear how drivers would get from the A2 to a Thamesmead bridge without lots of rat-running through Welling, Shooter’s Hill and Plumstead, and renewed pressure for the sort of “relief road” through Oxleas Wood that Labour fought so hard to stop in the 80s and 90s.

There are justified fears that any new capacity provided by a Silvertown Crossing will be quickly filled with “induced traffic” diverting from Rotherhithe, the Woolwich Ferry or the ever-rising tolls at Dartford. This could lead to the widening of the A102 and A2 and the demolition of homes in East Greenwich, Westcombe Park, Charlton and Kidbrooke. Tellingly, TFL won’t rule this out.

****

Blackheath Village: Ringway One would have put a six-lane motorway here had it not been stopped by a fierce campaign by articulate locals in the 1970s. If motorways aren’t the right solution to Blackheath’s transport problems then, why do we think they are the right solution to Thamesmead’s now?

As so often in Britain, social class is a barely-disguised elephant in the room. The crossings’ supporters argue that deprived east Londoners have had to wait too long for the sort of river crossings that rich west Londoners take for granted. In fact this argument can be turned on its head. While sections of the Motorway Box were built in poorer parts of London in the early 1970s, opposition to a six-lane motorway through the wealthy Blackheath Village meant that nothing was built before Labour won the GLC elections in 1973 and cancelled the schemes entirely. As Felix Barker, the Blackheath Society historian, noted acidly: “if you want to build a motorway in London don’t try to run it through an area whose residents include a future Prime Minister [Jim Callaghan, who had a London home in Blackheath], two future Ministers of State, the Cabinet Secretary, a future Chief Executive of Lloyd’s and a future Crown Court Judge.”

No-one now proposes building new motorway through Blackheath, Hampstead or Kensington as a solution to those areas’ chronic traffic problems: instead we try to restrain demand for car journeys by improving public transport, charging non-residents to park or (despite Boris Johnson’s retrograde decision to shrink the Congestion Charge zone) pricing people off the roads. It’s not clear why different rules should apply along the Thames in east London. As usual it’s deprived areas of London that become dumping grounds for the emissions of drivers who live miles away, don’t contribute anything to the local economy, and don’t have to suffer the environmental consequences. Why should residents of east Greenwich and Thamesmead – half of whom don’t own cars – have to put up with levels of air pollution and noise that no-one in Blackheath Village would tolerate? Why is TFL proposing the sort of urban motorway which places like Blackheath Village successfully resisted more than 40 years ago?

Probably because few of the consultants, politicians and business leaders who advocate new road crossings and motorways have to end up living next to them. Media commentators sneer at the lower Thames as “cockney Siberia”: somewhere where other people live. But under their noses is a unique opportunity to show how a city can grow and thrive without subservience to the private car. Let’s hope our politicians don’t flunk it.

Alex – that is a bit long and concentration starts to waver. couple of things – afraid this is all a bit historical

1. the lack of tolled crossings in west London is down to a decision of principle by the Government to buy out the tolls (which was done by the City of London from the Coal and Wine dues) and make ALL crossings free.

2. There is still a need for people to access jobs across the river. If you live in Sidcup and the job you are offered is at Whipps Cross you are going to have a pretty tough time.

3. There is a whole issue about public transport routes both cross river and generally throughout east London. In the early 20th century cross river public transport links were cut (closing Snow Hill Tunnel, cutting the East London Line link to Liverpool Street, and so on) mainly due to the separation of services between the London Passenger Transport Board and the still private railway companies, and later British Rail) . Since then there has been continued and deliberate fragmentation of the service between different types of transport – ie setting up DLR which could not interchange with either heavy rail, the underground, or the tube. (Actually heavy rail and the underground are the same but were separated administratively in the early 20th century, putting the underground together with the tube, which made no sense)

Don’t wonder we are in a mess.

I will try not to make remarks about transport planners – but I do understand they will not run more buses through the Blackwall because it is too busy and we all need to get out of our cars, first, and then wait to see if they put on a bus we can get, sometime.

– I’d better shut up before I get onto Moggeridge

Pingback: So long, Greenwich. I predict that by 2050 you’ll swallow up Lewisham and Bexley. The Thames Barrier will be a boutique hotel. And everyone will be mad as hell about air pollution | Alex Grant

Pingback: So long, Greenwich. I predict that by 2050 you’ll swallow up Lewisham and Bexley. The Thames Barrier will be a boutique hotel. And everyone will be mad as hell about air pollution | Alex Grant