News that the redeveloped London Bridge station has been shortlisted for the 2019 Stirling Prize will be treated with bemusement by many of its commuters. The reconstruction began in 2013 and was all but finished in 2017. It was officially re-opened by the Duke of Cambridge more than a year ago, in May 2018. As with most large infrastructure projects, Grimshaw’s new station has opened incrementally, but two-thirds of the new concourse, and several new platforms, opened to passengers in August 2016, nearly three years ago. It’s not clear why it has only been put forward for the Stirling now, some time after the last increment was opened.

News that the redeveloped London Bridge station has been shortlisted for the 2019 Stirling Prize will be treated with bemusement by many of its commuters. The reconstruction began in 2013 and was all but finished in 2017. It was officially re-opened by the Duke of Cambridge more than a year ago, in May 2018. As with most large infrastructure projects, Grimshaw’s new station has opened incrementally, but two-thirds of the new concourse, and several new platforms, opened to passengers in August 2016, nearly three years ago. It’s not clear why it has only been put forward for the Stirling now, some time after the last increment was opened.

Although the timing seems odd, the new station is easily the biggest project on this year’s Stirling shortlist (among the others are a house in Berkshire made of cork, a visitor centre at a Scottish whisky distillery, and 105 council homes in Norwich), and has a strong chance of being the final winner.

Anyone who regularly used the old London Bridge – as I did, for 20-odd years – will agree that the new station is a big improvement. The old station was a hellhole. The canopies of platforms 1 to 6, and the overbridge between them, had been rebuilt in the mid-1970s and perfectly symbolised the penny-pinching austerity of the time, clad in aluminium painted – for reasons unknown – in a shade of lavatorial brown. These platforms were too narrow, and only partly covered. There was no disabled access between these platforms, other than by going down and up long, and very overcrowded, ramps at their western end. The old Victorian trainshed over platforms 7 upwards had survived the 1970s revamp but was unloved, its glazing replaced by corrugated plastic, and cluttered with British Rail offices clad in opaque black glass.

Although London Bridge’s underground station had been rebuilt in the late 1990s, with the opening of the Jubilee Line extension, the only connection between platforms 1-6 and the tube station was via cramped, claustrophobic corridors whose ceilings often leaked: overflowing plastic buckets to catch rainwater were not an uncommon sight.

This poster extolling the merits of the station’s 1970s building is like a bad joke: London Bridge was a notorious bottleneck for another 40 years

In front of the station, the distinctive pyramidical skylights on top of the brown cladding were always far too small to let in much natural light to the bus stops underneath. Because London Bridge station stands on a viaduct many feet higher than the surrounding streets, it was curiously cut off from the local area: until the rebuilding of the tube station the only access was from Railway Approach, a dingy street by Guy’s Hospital. There was no direct access from the station to Tower Bridge (which is as close to the station as London Bridge is).

Above all, despite all the 1970s rebuilding’s promises that ‘The Stopper’s Coming Out’ of the ‘London Bridge bottleneck’, it remained one of the worst bottlenecks anywhere on the British rail network, with a dozen lines from across south-east London all converging and then criss-crossing each other on their way to Cannon Street, Blackfriars and Charing Cross. Just west of the station dozens of trains an hour competed for space on just two lines – one eastbound, the other westbound – at the Dickensian Borough Market junction, amidst the glazed rooves of the market beneath. While the market itself was reinvented in the late 1990s as an über-cool “go-to market” for Hipster street food, the railway infrastructure just a few feet above it had barely been modernised since the 1890s.

The 1970s revamp saw the removal of old signal boxes and the arrival of a computerised signalling system, but no new track capacity. By the 2000s, with the addition of Thameslink trains and increased frequencies on most of the lines that served it – from half-hourly trains to every ten minutes, even off-peak – London Bridge was struggling to cope. Platforms 1 to 6 were so busy that there was often only two minutes between trains, and the slightest delay could have catastrophic knock-on effects.

A solution to this chaos was a long time coming. Plans to rebuild the station and add track capacity, originally dubbed ‘Thameslink 2000’, were first put forward as long ago as 1991, but the project was delayed so many times that its hubristic name soon became a grim joke on commuters. Rebadged the ‘Thameslink programme’, with no date attached to tempt fate, rebuilding work finally began in 2009 with the construction of a new viaduct over the market roof, in effect bypassing Borough Market junction.

These CGIs, released in 2013, depict a new station rather more elegant and airy than what has been built

But in the medium term train services through the station had to get considerably worse before they could get better, with many lines seeing all their Cannon Street services switched to Charing Cross, or vice versa, and many trains passing through London Bridge without stopping at all.

Commuters through London Bridge station had long been the most phlegmatic in London, but even the considerable patience of Greenwich line passengers began to be tried beyond endurance when told that once the station was rebuilt they would lose direct Charing Cross trains for good (a major fault of the old station was the disruption caused by trains on the northernmost line to the east of the station having to cross over to its southernmost lines to the west). Although there are now more Thameslink trains than ever, offering manifold “new journey opportunities” – giving the Greenwich line direct trains to Luton Airport, for example – for many passengers this is scant consolation for the loss of a connection to Charing Cross, and thence the West End.

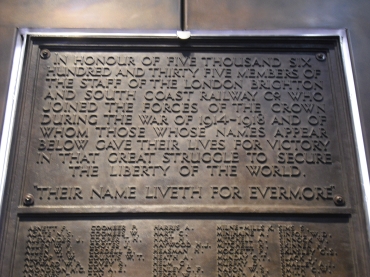

London Bridge’s First World War memorial has been reinstated – but much of the old station’s heritage has been erased

As a Labour councillor for 16 years until 2014, representing a ward served by the Greenwich line, much of my time was spent taking up commuters’ gripes with Southeastern Trains and Network Rail, both before and during the rebuilding (you can get a taste of the angst from several posts on my old councillor blog, to be found here, here and here). It is difficult to overstate the chaos these passengers faced at London Bridge between 2013 and 2018. The Jubilee Line – already full to capacity – was not much use as an alternative, entailing a long bus ride to North Greenwich station, marooned in the middle of the nowhere by the Dome. Nor was Crossrail, which was originally promised to be open in 2017 but has repeatedly been delayed until 2020 or even later. Even after sections of the new station were opened problems continued: the new concourse was described as “living hell” and “utter anarchy” in 2016; London Bridge was the epicentre of the Thameslink timetable debacle of 2018.

****

To be fair, that such an engineering feat was completed more or less on time, and on budget, is a significant achievement. Completely rebuilding such a busy station while trains still ran through it 20 hours a day has been justly likened to “open heart surgery on a patient – while they were jogging”.

So was five years of chaos worth it?

The lines into London Bridge station from the west, 1958

Firstly, it’s worth remembering just how old this station is. It is little-known that London’s oldest rail terminus is not Kings Cross or Paddington but unglamorous London Bridge, which first opened as early as 1836 at the western end of a four-mile railway to Greenwich (arguably London’s first commuter line). But lines westwards to Cannon Street and Charing Cross were opened in the 1860s, and ever since London Bridge has been more of a through station than a terminus: it is more often a station you pass through, or change trains at, rather than one you linger in before embarking on a journey. It was never great architecture. The Italianate main station building, designed by Lewis Cubitt (architect of King’s Cross station) opened in 1844, but its campanile was never completed. The station was largely torn down and rebuilt just five years later, in 1849, and largely rebuilt yet again in the 1860s. London Bridge lost its Victorian station hotel in the 1970s rebuilding, and even the most enthusiastic fan of Victorian rail architecture would hesitate to mourn the other buildings that were also demolished at the same time (they can be seen in the evocative 1958 photograph, above).

Rather like Victoria station, minus its continental glamour (no boat trains ever departed from here), London Bridge was historically two stations rather than one: a London Brighton and South Coast Railway terminus for some lines, and a South Eastern Railway through station for others. Platforms 1-6, for the through trains, were tacked on to the north side of the old Victorian trainshed as an afterthought.The two companies weren’t merged (to form the Southern Railway) until 1923, and until the 1970s overbridge was built there was no connection between the station’s two halves: anyone changing trains had to go through the booking hall to the west to get from one to the other. But platforms 1 to 6 soon became much busier than the platforms in the trainshed itself, which was often eerily quiet until its demolition a few years ago (the new station has resolved this by increasing the number of through platforms from six to nine, and reducing terminus platforms from nine to six).

The 1862 trainshed, now demolished, though parts of it may yet be re-erected in Aberystwyth

London Bridge is to south-east London what Clapham Junction is to south-west: a bottleneck through which all trains must pass. London Bridge station has always been a very busy station: even before its latest rebuild it was London’s fourth busiest, with 53 million passengers arriving or departing in 2012-13, not too far behind Waterloo (96 million), Victoria (77 million), and Liverpool Street (58 million), and considerably busier than Charing Cross (38 million) Euston (38 million) and Paddington (34 million). London Bridge is no backwater: it is in fact closer to large parts of the City of London than Liverpool Street station is, and those iconic photographs of suited City workers walking across London Bridge mostly depict the station’s passengers, choosing to complete their commute on foot rather than on the Northern Line.

Waterloo Station is famed for its Victory Arch and the London Necropolis Railway that took coffins straight to Brookwood Cemetery; Paddington has its Brunel trainshed and its bear. Euston is haunted by the ghost of its demolished arch. Victoria is haunted by the many thousands of First World war soldiers who left for the Western Front from its platforms, never to return, and the many visiting heads of state for whom it was a ceremonial arriving point. By contrast London Bridge has always been curiously overlooked. Despite its central location and iconic name, the station is strangely short of cultural references.

Operation London Bridge (the codename of the Queen’s much-rehearsed funeral preparations) is named after the actual bridge, not the station. Likewise, the old nursery rhyme London Bridge is Falling Down refers not to the shabby railway station but to the medieval incarnation of the bridge, before it was rebuilt in the 1830s (the current bridge is in fact very modern: John Rennie’s five stone arches were infamously sold to an American oilman, Robert P. McCulloch, in 1968, and re-erected at Lake Havasu City, Arizona in the early 1970s, to be replaced by a utilitarian structure with heated pavements). When London Bridge is Falling Down appears on TV or in children’s books it is often accompanied not by a picture of any of London Bridge’s iterations, but by a cartoon of Tower Bridge, half a mile downriver. If the bridge after which it is named can be so invisible, London Bridge station does not stand a chance.

Both these old wall remnants -from the 1862 station rebuilding (left) and of the original 1836 station (right) were demolished in 2012-13

Unlike Paddington, Victoria or St Pancras, London Bridge rarely features in films, TV or novels. John Davidson’s turn-of-the-century doggerel poem London Bridge – one of the few times the station has been mentioned in verse – is hardly laudatory: “Inside the station, everything’s so old/ So inconvenient, of such manifold/ Perplexity, and, as a mole might see/ So strictly what a station shouldn’t be/ That no idea minifies its crude/ And yet elaborate ineptitude.”

This station simply isn’t famous, and is rarely used as a metaphor for anything. This is odd as London Bridge station symbolises many things: 1970s bungling, penny-pinching, chronic overcrowding, and the unsurpassed ability of the London commuter to tolerate squalor with little complaint. For so many decades of commuter misery to be worth it, the new station must be very good indeed. It must stand the test of time and should not need to be rebuilt yet again in our lifetimes. And it should be accompanied by world-class public spaces both in the station, and around it. On all these counts, the jury is still out.

These elegant arches on Tooley Street have also been demolished

We have been here before, of course. Looking back at publicity for the station’s last rebuilding between 1972 and 1978, it is striking how confident British Rail was that the ‘new’ station would solve problems once and for all. Although it is now seen as a failed 1970s experiment, at the time the ‘new’ station was billed as a permanent cure, not a temporary sticking plaster. The 1975 British Transport Film Operation London Bridge (a term yet to be appropriated for the death of a monarch) now seems laughable. With its Maurice Jarre-style music and footage of pipe-smoking British rail managers, flat-cap wearing workmen lifting sleepers, and south London schoolchildren – almost all of them white – singing London Bridge is Falling Down, it demonstrates just how much British Railways, and their public relations, have moved on since privatisation.

Yet much of the script sounds eerily familiar. Its descriptions of the old Victorian station as “confused and confusing… bleak and uninviting”, could just as easily be applied to the rebuilt station it heralded. Its promise of “a spacious new concourse with its own bars and shops”, and its description of the ‘new’ 1970s overbridge as a “welcome improvement on the damp underground passages of the past” could just as easily be applied to the latest rebuilding.

The new concourse allows plenty of space for light to filter down from the platforms above

Will the new station stand the test of time better than the 1970s one? While Grimshaw is undoubtedly a world-class architectural practice, it has a patchy record at London rail termini. Grimshaw’s work at Paddington in 1999, billed grandly as “Phase 1 redevelopment”, was really little more than a revamp of the concourse. Its International Terminal at Waterloo, opened with much fanfare in 1993, was soon bursting at the seams, and closed 14 years later when Eurostar trains were moved to St Pancras. The terminal’s underground waiting areas were always poky, and while its serpentine trainshed roof was admirable, it always jarred with the rectilinear roof of the Edwardian station alongside. It was long one of the British railway’s biggest white elephants until its platforms were finally put to commuter use in 2018-19. Grimshaw’s proposed HS2 terminus at Euston has yet to get off the drawing board, and with the whole HS2 project under the spotlight from Boris Johnson’s new administration, it may never be built at all.

Grimshaw boasts that the new London Bridge station “incorporates its layers of history by adaptively reusing spaces where we can and only creating new ones when we can’t”. The architects make much of the “shop-lined Western Arcade, historically a site of an market when the station was first built, which has been tripled in size with new concrete quadripartite arches, “referencing the rich brutalist heritage of the South Bank”, alongside the original Victorian brick ones. It is great that this previously hidden space has been opened up. But all the arches are covered at ground level (the concrete ones with perforated corten-steel, the brick ones with perforated concrete), presumably to avoid wear and tear. When I first saw the cladding several years ago I assumed it was temporary, but it’s clearly a permanent, and unsatisfactorily messy, solution.

The new arches on St Thomas Street will please some. But many original Victorian arches have been demolished here

Victorian arches have been restored and replicated at the southern side of the new concourse, giving street-level access to the station from St Thomas Street for the first time. But many have criticised the detailing of the brick there. As the Observer’s Rowan Moore wrote in his review of the station back in 2016, “Curves don’t quite sweep as they might and edges you might want sharp are blunted”.

Elsewhere, many remnants of the Victorian station that survived the 1970s rebuilding have been demolished, not restored. For all the rhetoric about having “respected its Victorian heritage”, a lot of eggs had to be broken in the making of this omelette. On St Thomas Street, many of the original tripartite arches have been demolished. The Southeastern Railways offices at 64-84 Tooley Street – designed by Charles Barry Jnr in 1893 and once dubbed as London’s answer to New York’s flatiron building – were flattened, unnecessarily, to improve access from the new concourse to the bland More London development and Tower Bridge beyond. But the rather pointless paved area that now stands here is cluttered with concrete barriers to stop terror attacks. TP Bennett’s original masterplan for the station had the concourse slightly to the west of its current position, which would have allowed it to survive. More London Place, the pedestrian route that links London Bridge station to Tower Bridge, used to have this Victorian building as its western end; now it only has the dull horizontality of Grimshaw’s new station. Boris Johnson has been widely mocked for having reportedly suggested gargoyles for this elevation, but maybe he had a point: it’s all rather boring.

Above the new concourse, its undeniable that unifying the two halves of the old station made retention of the 1860s barrel-vaulted trainshed difficult (even English Heritage accepted that it had to go). But it’s a pity that only a third of the old trainshed, and 16 of its columns, were salvaged. In 2013 much was made of the news that Network Rail had agreed to donate part of the trainshed to the Vale of Rheidol Railway, who promised to re-erect it in Aberystwyth. But as of 2016 Rail Engineer magazine reported that part of roof was “now stored at the Vale of Rheidol Railway in Wales where it may be rebuilt at a later date”, and as of 2019 there is no mention of London Bridge station trainshed on the Vale of Rheidol Railway’s own website. All in all it’s a casual, slapdash way to treat a Grade-2 listed structure.

On Tooley Street, Charles Barry Jnr’s Southeastern Railway Offices of 1893 have also been demolished

The new station’s highlight – its huge lateral concourse, across the station from north to south – is undeniably impressive. The space for passengers to mill about it while waiting for their trains must be ten times bigger than at the old station, and the number of concrete columns – likened by some to Barbara Hepworth sculptures – has been minimised, to maximise space for passengers. Nadia Broccardo, chief executive of the local business improvement district ‘Team London Bridge’, has said the station is becoming “A place to go to, not through”. Having such a concourse at street level, directly below the platforms, is unusual at British railway stations but very common in Europe, and London Bridge now more closely resembles the hauptbahnhöfe of German cities like Munich or Dusseldorf than any other London termini.

Natural light from the platforms spill down into the concourse via generous wells for escalators and steps: the station is now fully accessible for wheelchair users. For the first time there is now a proper pedestrian route from Tower Bridge to Guy’s Hospital, via the new concourse: previously the only way was through the dingy Weston or Stainer Streets, under the viaduct to the east of the station, or a big detour on the busy, narrow pavements of Borough High Street.

The new station’s concrete columns have been likened to Barbara Hepworth sculptures

As two Architect Journal award judges have put it, the new concourse ‘reconnects the tissue of the city’ and is “a great piece of urbanism beyond its job as a station’. But the predominant material in the new concourse is acres of diagonal red cedarwood, and it remains to be seen how well this flimsy cladding will weather if not scrupulously maintained. Making the station more navigable and legible should make most signage redundant, but a Network Rail bureaucrat appears to have insisted on far too many departure boards and dark-blue overhead signs (some saying ‘the lift is behind you’) that clutter the concourse unnecessarily.

Upstairs there’s an equally fine secondary concourse linking the terminating platforms to the new bus station. But nothing feels or likes quite as fine as the CGIs promised. Above the new platforms themselves, it’s disappointing that there are only canopies linked by strange wavy bands (apparently put in at the insistence of a planning officer). The modular architecture has a “somewhat clunky, Meccano-esque quality”, according to Blueprint’s Veronica Simpson. Although Grimshaw describes these canopies as a “series of ribbons” that look like a single structure when seen from the upper floors of the Shard, from underneath they look as if the intention was to have a fully-covered station until the money ran out. The station should make up its mind about whether it is an indoor space or an outdoor one. Grimshaw partner Mark Middleton has said that there was no need for an ‘overall’ roof “because passengers aren’t going to linger around to enjoy it,” which won’t impress anyone waiting for a delayed train.

All that timber in the new concourse could look awful if it is not scrupulously maintained. And everywhere there is excessive overhead signage

The station’s traditional entrance (on Railway Approach) is now much better without the covered bus station that used to stand there. But this is a low bar. The two new buildings that overlook the station’s forecourt – Renzo Piano’s Shard to the south and his ‘baby Shard’ to the west – are widely hailed as improvements on the two towers that they replaced (TP Bennett’s Southwark Towers of 1975 and Richard Seifert’s New London Bridge House of 1967). But neither the Shard nor its baby meet the ground well. The Baby Shard is an inelegant stump of a building that looms over the historic St Thomas Church, whose building dates back to 1703 and the Georgian terrace alongside it: you almost wish it had been built as a proper shard, not an iceberg.

Oddly, neither building seem at ease with their modernity: the lower floor of the baby Shard, and the shopping arcade beneath it, is decked out in cheap yellow brick that jars with the glass and steel, and does not even faithfully resemble the old London stock brick of the station’s arches. The glass canopies that jut out of the Shard’s lower stories look flimsy and value-engineered, and do not make the adjacent station’s passengers feel valued.

The new platforms are a huge improvement on the old. But why the unglazed struts between the canopies?

The space between the station, Shard and baby Shard should be an important new public space, of the highest quality. But although new trees have been planted here and a fussy booth selling bus tickets has now been removed, the area is still cluttered with bulky car-bomb proof bollards, and the bus stops look cheap and nasty. The baby Shard, which oversails part of the bus station, drops huge structural columns into the middle of its narrow waiting areas. As a place to wait for a bus, its only slightly more pleasant than the shit-brown bus station that used to stand here. It would have been better if all bus stops had been moved to adjacent streets, as at Victoria.

There are, surprisingly, uninterrupted vistas from here of Southwark Cathedral, the dome of St Paul’s and the key modern buildings of the City – the Gherkin, the Walkie Talkie and Seifert’s NatWest Tower (maybe as a favour to Hitchhikers’ Guide to the Galaxy fans, it’s now officially called Tower 42) – but there is no orientation to tell visitors that they can see six London landmarks if they look carefully. A competition was held last year “to improve the streetscape and assist wayfinding” at the station’s northern exit on Tooley Street, but the money would be much better spent here. Remarkably, pedestrian connections between London Bridge station and the bridge itself remain poor: although London Bridge Walk, the horrible concrete pedestrian bridge over Tooley Street, has finally been closed, the pavements of Railway Approach – the most direct route from station to bridge – are just as grotty as ever as they pass under the railway lines.

The new public space on Railway Approach, at the foot of the Shard, should be world-class. But it’s full of bus stops, and the pedestrian route from the station to London Bridge itself is as grotty as ever

London Bridge has always been a chaotic station, constantly being rebuilt on the cheap ever since its opening in 1836. Its latest incarnation is certainly less cheap, and more ambitious, than any of its predecessors. But a new railway station that is so much better than its predecessor is not automatically a great building. London Bridge Station is skilful engineering, not world-class architecture. It has already received several gongs, winning the 2018 New London Architecture awards and the 2018 World Architecture Festival’s ‘Transport Completed Buildings’ category; being named as Architects’ Journal’s Building of the Year and as RIBA London Building of the Year for 2019. Does it really also deserve British architecture’s highest accolade of all?

With old London Bridge you could get from the low level platforms to the Greenwich line platform in 2 minutes on the overbridge. Now it’s a long long walk. Disgracefully bad design

Totally agree Mary. Said it the first time I used the ‘new’ station. Down and up those long escalators to change platforms is such a palaver compared with using the old overhead connecting walkway. Not thought through properly. Very poor design.

Started using London bridge in 1987 for 20 odd years. A dramatic improvement and construction restrictions must have meant compromises to its elegance. My only negative is the station platforms (I think) are much colder and windier than before.

Bit SJW snow-flakey – why the reference to white workers in the 1970s, are you trying to judge 40 years ago with today’s morals or something? – but I agree the new station looks more like a large hotel than a train station and it takes too long to cross. But the old station was worse, unless you like Soviet living I suppose.

Oh, and I guess your review of the video didn’t include the reasonably broad cross-section of races in the children’s classroom – for 1975 – right at the very beginning. Bit selective.

Thanks for your comments Ady. I actually find the footage of London schoolchildren singing London Bridge is Falling Down rather touching. I just feel it is poignant given that a) the 1970s rebuilding of the station was obselete within 40 years of its completion and b) that no such infrastructure project would include such footage in a promotional video today. My observation that “almost all” of the schoolchildren were white was not criticising the film, or accusing its editors of excluding non-white faces, but simply to point out that Southwark was so much less racially diverse than it is now. No SJW snowflakery from me: I save that for serious issues!

Dear Alex Grant, I am preparing a short article ‘Steaming to London Bridge’ for the magazine The Southern Way, published by Crécy. I spotted a photo on your website – ‘The Lines into London Bridge from the West, 1958’ which I could use in the article (or a similar photo from the tower of Southwark Cathedral). Do you own the image and its copyright? If not, could you tell me its ownership with address, please?

With thanks, Alan Postlethwaite

Thanks Alan, I borrowed the image as ‘fair use’ for purposes of commentary, criticism, reporting, and teaching. I think it is officially a Getty Image – see https://www.gettyimages.in/photos/london-bridge-station – so you will need to approach them for copyright permission if you want to use it in a commercial magazine. Best wishes, Alex