A screeching U-turn on long-term care bills. Uninspiring, robotic TV appearances – and several non-appearances at leadership debates and Today programme interviews. An inability to think on her feet, answer unscripted questions from the public, show herself as a team player, or display a smidgeon of humour, courage, imagination or even humanity.

A screeching U-turn on long-term care bills. Uninspiring, robotic TV appearances – and several non-appearances at leadership debates and Today programme interviews. An inability to think on her feet, answer unscripted questions from the public, show herself as a team player, or display a smidgeon of humour, courage, imagination or even humanity.

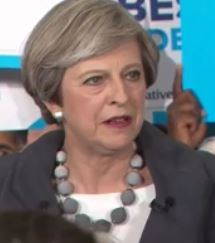

The charge sheet against Theresa May is long, and no matter how well the Conservatives do at the ballot box tomorrow her flaws have been brutally exposed during this campaign. Margaret Thatcher, John Major, David Cameron, Michael Howard and even William Hague were all far better on the campaign trail.

It’s often been pointed out that the Tories have fallen from a 18-point opinion poll lead at the start of the campaign to an average lead of just 5.7% in the last seven days. But a 12% fall in the Tories’ lead does not mean a fall of 12 points in Tory support. In fact, the Tories have been in the high to mid forties in almost every poll, and have only fallen by about 3-4% since the campaign started. Even after a poor election campaign fronted by the increasingly wooden Theresa May, this BBC graphic shows the Conservatives are, on average, still well ahead of their standing in almost every poll in the last year of Cameron’s premiership.

So Labour’s rise in the polls – from the low 30s at the start of the campaign to the high 30s now – has not been at the expense of the Tories, but from the faltering Lib Dems, don’t knows and possibly UKIP (although most of their supporters drifted back to the Tories soon after the referendum last June).

With UKIP and the Lib Dems so low – latest polls give the Lib Dems 9% at most, UKIP 5% at most – politics in England and Wales (albeit not Scotland) has reverted to its two-party norm. The trouble for Labour is that although its status as the main opposition party is no longer in doubt, to have any chance of winning outright in such a two-horse race they need to be in the 40s. Yet of the ten polls published since June 1st, only two have put Labour at 40%, and two others have put Labour at just 34%. One of these ten polls has shown the Tory lead at just 1%, but five others have shown the Tories ahead by 8% or more. No opinion poll has put Labour ahead of the Tories since April 2016. And since the campaign started just one “analysis” by YouGov – not an opinion poll at all – has predicted a hung parliament (with the Tories still the largest party) using new, and controversial, methodology.

All these polls point to one conclusion: the Tories may not win by as great a landslide as they once hoped for, but they’ll almost certainly increase their number of seats tomorrow, ending up with a majority of between 30 and 100 (even YouGov’s top two experts, Anthony Wells and Peter Kellner, expect a Tory majority of between 65 and 70). While Labour’s rise is impressive, it’s been too shallow, and from too low a base, for Jeremy Corbyn to have any chance of entering Number Ten, even as part of a grand coalition. Labour may win back some of the seats they lost in Scotland and Wales in 2015, and may even gain some urban seats such as Croydon Central or Leeds North-West. But some of these gains will be from the SNP and the Lib Dems, and will inflict no damage on the Tories’ majority. And any gains will almost certainly be offset by losses in outer London, the Midlands and the north.

Given the dreadful errors the Tories have committed during the campaign, the wonder is not how badly the Tories are doing in the polls, but how well. Compared with the run-up to the 2015 election – in which the Tories and Labour were neck and neck, with several polls showing Labour ahead by up to 6% – the Tories are cruising to victory this time, not spluttering.

Labour’s only hope rests either on a last minute surge in support (so far undetected by any opinion pollster), higher than expected turnout by young people (which failed to materialise in either 2010 or 2015), or over-compensation by opinion pollsters after 2015. Since most pollsters’ failure to predict the Tories’ victory, most of them have adjusted the weighting of their polls to allow for more “shy Tories” – those who vote Tory but are reluctant to admit it, even to a confidential opinion poll. At this stage of the campaign, all these hopes are clutching at straws. I’m voting Labour tomorrow and part of me hopes my pessimism is misplaced, but I’ll eat my red rosette if Labour wins outright. I predict a Tory majority of 55.

****

Why then have the dominant stories of the last fortnight – other than the recent terror attacks of course – been the failure of the Tory campaign, not its success, and the possibility of a hung parliament or even a Labour victory?

Almost as prevalent as May’s “Strong and stable” mantra has been the media’s ‘confirmation bias’ – the tendency to misinterpret data to confirm pre-existing hypotheses, or unearth an exciting new story – during this campaign. Opinion polls showing the gap between the Tories and Labour narrowing have been seized on by the media, and by Jeremy Corbyn’s supporters, as firm evidence that Labour is on course to pull off a historic comeback. Just ten days ago the Guardian even ran a story entitled ‘Guardian/ICM poll: Tories’ 12-point lead offers Labour crumbs of hope’, because the poll had shown Labour had regained its lead among the unskilled working class (by 43% to 36%) and among 25-to 34-year-olds (43% to 34%) for the first time in the campaign. Only later did the story mention that the poll also showed the Tories with a commanding lead of 64% to 20% among over-65s.

And it’s not just Labour-leaning outlets like the Guardian that have been exaggerating Labour’s hopes – it was the Times, not the Guardian, that splashed on YouGov’s analysis that the Tories could lose seats rather than gain them. What is remarkable is not how badly Labour had been treated by the media, but how leniently: even the ritual hatchet jobs by the Sun and Mail have flattered Labour by implying that there is a real possibility the party can win.

It’s understandable that journalists have been trying to make the race look tighter than it is. Despite the off-stage distractions of two appalling terror attacks, the campaign itself has been one of the dullest on record. Only the schadenfreude of Corbyn and Diane Abbott’s fluffed interviews will stick in the memory. There has been no great oratory, no dramatic surprises other than May’s U-turn on long-term care, and despite the media hyperbole there hasn’t even been a dramatic shift in the polls – just a gradual tightening, as almost always happens in British election campaigns.

****

On the ground it’s clear that this election is being fought on very different territory – both politically and geographically – from 2015. My home seat of Corby and East Northamptonshire – half steel town, half prosperous Tory-leaning villages – has been a bellwether ever since its creation in 1983. But this time it’s been ignored both by the media and party leaders (Corbyn has been to Leicester and Peterborough, both 20 miles away, but has not set foot in Corby, though John Prescott has).

Corby had been briefly Tory between 2010 and 2012, when its MP Louise Mensch moved to New York and Labour’s Andy Sawford won a by-election with an astonishing 48% of the vote. In 2015 it was thus deemed to be a safe(ish) Labour seat, and Tom Watson is rumoured to have vetoed giving it a lot of resources from HQ. Unexpectedly, in 2015 it was won by a 26-year-old Tory from nearby Wellingborough, Tom Pursglove, with a majority of just 2,400. But in 2017 Corby’s deemed to be out of reach: Labour is only putting resources into Tory-held seats with a majority of 2,000 or less, I’m reliably informed. Corby’s hard-working Labour Party, and its excellent candidate Beth Miller – a twenty-something born and bred in Corby and now working for the Bank of England – are on their own.

That a seat held by Labour from 1997 to 2010, and again from 2012 to 2015, is now deemed to be unwinnable says much about Labour’s woes. In the 1990s and 2000s Labour would concentrate heavily on large towns in the Midlands and south-east – Corby, Northampton, Milton Keynes, Reading, Peterborough, Ipswich, Swindon and Plymouth, among others – as these were the places where elections are won or lost. But apart from a few quixotic outings to places like Great Yarmouth and Watford (both seats that haven’t been won by Labour since 2005), Corbyn has concentrated on seats that Labour clung on to in 2015. The battleground has shifted away from the south, into the north Midlands and Yorkshire, where even Newcastle-under-Lyme and Derbyshire NE – seats held by Labour since 1919 and 1935 respectively – now look vulnerable.

Many eyebrows were raised by Corbyn’s tour of supposedly safe Labour seats in the north-east in the last 72 hours of the campaign. It’s obviously heartening for Labour to have attracted a crowd of 10,000 to its rally in Gateshead on Monday, but it should always attract such large crowds in such a Labour stronghold. Events like these might lift the sprits of Labour campaigners but they do little to win over floating voters, let along swing marginal seats.

Theresa May, by contrast, has visited a slew of safe Labour seats in the last week: Hemsworth (Labour majority 12,078), Don Valley (8,885), Penistone and Stockbridge (6,723) and Bradford South (6,450). As the New Statesman’s George Eaton has shrewdly observed, “This is not the itinerary of a leader fearing defeat or a hung parliament”.

If the Tories’ performance is at the bottom end of expectations – say a majority of only 30 or 40 – there will be many who argue that Corbyn should stay on as leader, particularly if Labour’s share of the vote is higher than the 29% that the party notched up under Ed Miliband in 2015. Back on May 16th Left Futures – a blog edited by the Corbynite Jon Lansman – even argued that any improvement on Labour’s 2015 vote share “would prove hugely embarrassing for those who have attacked [Corbyn] as ‘unelectable’ over the past two years… even if insufficient to form a government”. Settling old scores with the Blairites is obviously a higher priority than winning a general election. While the Right looks for converts, the Left has been busy looking for traitors.

Such loyalists need to remember that political parties exist to win and hold power, not to continually find excuses for failure. With the NHS and social care in crisis, confusion over Brexit, and a weak and wooden leader, the Tories could and should be beaten in 2017. If Labour fails to win it has only itself to blame.

Pingback: To win next time, Labour must overcome its Midland problem | Alex Grant